The unification of Germany in 1871 constituted a watershed

in Germany’s imperial agenda of acquiring colonies in Africa. A number of

lobbying groups formed after the unification, including the West German Society

for Colonization and Export (1881) and the Central Association for Commercial

Geography and the Promotion of German Interests Abroad (1878). These groups

exerted pressure on the government to acquire colonies abroad, especially in

Africa, by arguing that Germany needed the territories to maintain its economic preeminence. The result was the founding of the

German Colonial Association in 1882. The expansion of German industry and the

growth of German maritime interests facilitated a more aggressive colonial

program. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) was initially not a colonial

expansionist, but he changed and signed on to the demands of the lobbying

groups for a more proactive role in the race for colonies. Bismarck became

convinced that it was imperative for Germany to move quickly if the country was

to protect its trade and economic interests because of the emerging

protectionist policies that would come with colonialism. This position was best

articulated by the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce in 1884 when it

asserted that if Germany were not to forever

renounce colonial possessions in Africa, especially the Cameroon coast, then it

had to act swiftly by acquiring the territory.

Annexation of territory was a significant feature of

the emerging protectionist imperial world order of the late nineteenth century.

In addition, the prevailing international situation strengthened Bismarck’s

resolve to acquire territories in Africa. The British occupation of Egypt in 1882 and

imperial incursions by France into Africa and Asia combined to make the issue

of colonies a national necessity that had to be embraced by Germany because of

its preeminent role in continental European diplomacy and politics. Being the

skillful politician he was, Bismarck also envisioned the politics of German colonies

serving as a stabling force in domestic politics by emphasizing nationalism and

the greatness of Germany internationally. Bismarck was a pragmatist and his

drive to acquire colonies in Africa was largely a function of economic

considerations, both real and potential, in the emerging imperial world order, European

diplomacy, and domestic politics as well.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 to 1885, hosted by Bismarck,

was a turning point because it not only recognized European colonial claims in

Africa but also hastened the process of partition. The European powers agreed

that those nations claiming parts of Africa had

to physically occupy them in order to legitimize

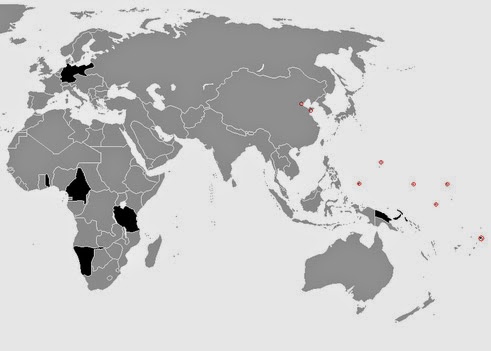

those claims. Germany annexed South West Africa (present day Namibia) in 1884

after negotiations with Great Britain. In the same year Germany annexed a strip

of coastline on the Gulf of Guinea, which was later expanded into the territory

of German Cameroon. The acquisition of Togo completed German annexation of territory in West Africa. Germany acquired German East

Africa (present-day mainland Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi) in 1885, and a

formal protectorate was declared in 1890. However, formal boundaries were not concluded

until the late 1890s.

Germany used concessionary companies during the infancy

stages of establishing a colonial presence in the annexed territories. The

companies were granted charters to administer the colonies on behalf of the

German government. The concessionary firms were supported on the grounds that they would mobilize private

capital for the purpose of investment in the colonies. The argument was that

private enterprise would be less costly, both to the government and taxpayers,

since the latter two would be spared the burden of financing the empire.

In South West Africa, German imperial interests were

advanced by the German South-West Africa Company and in East Africa by the

Imperial German East Africa Company. The companies failed to perform as expected

because of two main factors. First, the companies lacked a strong capital base to undertake the various

governmental functions, including constructing the infrastructure required for

colonial control. Second, the companies were ill-equipped to contain uprisings during

the initial stages of establishing imperial control.

By the end of the 1890s, direct governmental control

had supplanted administration by concessionary companies. Germany developed a

reputation for ruthlessness in dealing with uprisings in its colonies. The

Herero Uprising of 1904 was ruthlessly suppressed, resulting in the deaths of

nearly sixty thousand out of a population of eighty thousand. The Germans not

only shot the victims but also poisoned the water holes from which survivors could

have drawn water, resulting in the deaths of thousands more. Those who survived

were forced into work camps and became the subject of various medical

experiments and examinations.

In German East Africa, the Abushiri Revolt was ruthlessly

suppressed in 1889. The same fate befell the Hehe community following an

uprising in 1893 when their leader, Mkwawa, was arrested and hanged. The 1905 to

1907 Maji Maji Rebellion in southern German East Africa was equally stamped out

when Germans resorted to a ‘‘scorched earth’’ policy that resulted in killings,

as well as a massive destruction of crops. The Duala resistance in Cameroon was

brutally suppressed. In Togo, the Dagomba fiercely resisted German intrusion,

but were overwhelmed. The colonization of African territories

by Germany was to a large extent achieved through forceful means, which

included overt military campaigns, economic coercion, and land seizure and

expropriation.

After the colonial wars of pacification, Germany proceeded

to institutionalize political and economic control by putting in place an

administrative structure. The colony was headed by a governor. The commanders

of the armed forces in the colony, although answerable to the governor,

retained a lot of power because they were subject to the High Command in

Berlin. The military performed the vital function of maintaining power

relations in the colony. A number of the officers also doubled as regional

administrators. African chiefs were appointed and made subject to the authority of the local

German officials, who were invariably few. The chiefs were supposed to

undertake such functions as collecting taxes, conscripting labor for colonial

projects, and enforcing government policy. The Germans established a colonial administration

that embraced both direct and indirect rule that varied from one colony to

another, and on occasions even within the same colonial territory.

The administration of justice in the German colonies

was anything but impartial. Its function was to maintain the status quo on the

erroneous premise that Africans were inferior, which led to the degrading

practice of corporal punishment as well as the frequent arbitrary executions in

the colonies. The Germans developed public hospitals as well as educational

institutions. But even in these two areas, the facilities were inadequate to cope

with the large number of people who desired health and educational services.

The German colonial government encouraged the participation

of missionary societies in the provision of these services. The situation in

the German colonies was hardly dissimilar from that in other European colonies

in Africa. German colonial rule was still evolving by the

time World War I broke out. Africans were

conscripted to fight on various warfronts in defense of German imperial

interests. However, the end of the war in 1918 proved disastrous for Germany’s

imperial ambitions in Africa. Germany was defeated and forced to surrender all its colonies, which were subsequently taken over

by the other European imperial powers—Britain, France, Belgium, and in the

context of South West Africa, South Africa.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baer, H. M. Carl Peters and German Colonialism: A

Study in the Ideas and Actions of Imperialism. PhD diss., Stanford University,

1968.

Boahen, A. Adu, ed. Africa Under Colonial

Domination, 1880– 1935. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. Abridged

ed., 1990.

Smith, W. D. ‘‘The Ideology of German Colonialism,

1840–1906.’’ Journal of Modern History 46 (1974): 641–663.

Stoecker, Helmut, ed. German Imperialism in Africa:

From the Beginnings Until the Second World War. Translated by Bernd Zollner.

Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International, 1986.

Wesseling, H. L. Divide and Rule: The Partition of

Africa, 1880–1914. Translated by Arnold J. Pomerans. Westport, CT: Preager,

1996.